Testimony of Sara M. Flanders

(VIII. 61)

In the first place, it may have puzzled you when I continued to stay in Europe when this was going on, and I would like to explain why I did. I did not know anything about it. My husband knew perfectly well that if I knew about it, I would take the next boat home. So, anyone who was likely to write to me was warned, and when I arrived in New York, I saw various people. Nobody said anything. I went to visit my sister in Providence, and nobody said anything.

The only false note that occurred the whole time I was on my way home, the entire time I was away, was that Joe Stein, of whom you have heard, the cellist with whom we played for many years, called up from Boston, which was reasonable enough, called up, knowing I was to be in Providence, sorry not to see me, and he said, "As soon as you get to Chicago, send me Ellen's address, and let me know how Ellen is." I said, "All right." And he said, "I do want to know how Moll is, and why he hasn't written to me."

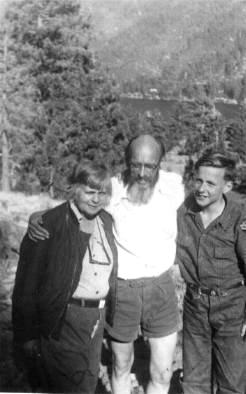

Sally M., Donald and Steve Flanders

I simply roared. I said, "He hasn't written you because he never writes to anybody." But it seemed strange that he, knowing that Moll never writes a letter would ask about it. That is the only thing that made me feel there was anything curious about it. Then it wasn't until we had been home, and Steve had finished burbling as much as he could in the first half hour--I guess until Steve was gone that I learned about it.

The reason that I went to Europe was that Jane was planning to study in Paris. Each of the three older children was left a thousand dollars to do as they wished when they got to be 21. Jane decided she would spend hers on a year in Paris studying music. The she, not surprisingly got cold feet during the summer, and thought it was going to be very far away, and my sister suggested that I go with her and get her settled in Paris. I said that was perfect nonsense; we didn't have the money. Everybody insisted so strongly that I finally investigated to find out whether Steve could go half-fare, and finding that he could go half-fare, this year and next summer, allowed my sister and others to persuade me and went. I was very glad I had because the fact that I was on the boat with her, which was a French boat, meant that I made friends with three Frenchwomen, Parisian women, who were my age, who were glad to be nice to Jane because they had made friends with me, but would never have noticed her otherwise. She would have been one of the many kids on the boat. So I stayed ten days in Paris and got her settle, and Steve and I saw sights. Then I left her feeling very happy about her because she had older friends and also friends of her own age in Paris.

Q. Have you ever been a communist sympathizer?

A. Well, at the time of the original Russian revolution, I read the new constitution, and thought it was probably the most superb document that I had ever read, ever been written.

And then as time went on, it seemed to me that they were, that it was a pretty piece of paper, and for a long time, I guess probably to the time of the purges, I felt they had demonstrated and done great things in Russia. At the time of the purges, I could not see how they could be justified, and from that time on, I lost more and more sympathy with them.

Also while we were in Denmark in 1937-38, I remember talking to Professor Harold Bohr, who said that among the people he had helped or knew about, I am not sure whether he had helped them to get to Russia. They had gone to Russia feeling as I just said I did, that it was a fine place to escape to from Germany or such, and then had found that life was fully as difficult and as, well

VIII. Sara M. Flanders 62

as impossible in Russia as it was in Germany. That backed up my--I read Dodd--I am terrible about names and dates--and he tried to justify certain and succeeded in justifying some of the people as having worked against the government. But he couldn't convince me that it was all right, and, and Bohr's statement made me feel still more that the situation in Russia was not all right. In other words, I began at that point to feel that the communist constitution was a piece of paper, and I have never felt much sympathy for them since then.

Q. Your attitude towards Soviet Russia from the date of the purge to date was non-sympathetic?

A. Yes. Well, not even down to date as that way. At that point I was non-sympathetic, although I did feel there were probably certain things about it that were still of value. Then I was, of course, very much impressed with the defense of Stalingrad, and thought they were doing a good job there.

I can't exactly put my finger on when I began to completely anti, but it certainly was at the end of the war. I was anti and very shortly after that I became very definitely anti.

Q. Do you draw any distinction between communism and socialism?

A. There again I would say that it was a fine piece of paper, that the theory of socialism was excellent, but not necessarily workable, and certainly not probably workable then here. After all, Norman Thomas is about as good a symbol of futility as we have. He is a perfectly fine person, with fine ideals, and he has tried awfully hard and accomplished very little.

Q. Did you ever register as a socialist?

A. Sure. It was the time of--it was 1929 when we came to New York. The crash was in 1930. I would say that it was in the winter of 1930 or 1931 that people were starving in New York City, and the socialists were definitely doing something about it. I think it was Priscilla that came and asked me if I wouldn't help collect old clothes in my building, and help serve refreshments in the socialist headquarters. But I didn't join until the following year. I just went over and brought clothes and passed them out. I joined them, though, and it was extremely dull. I don't remember resigning, but I just stopped. I let it ride and was too busy with the family, the kids, to do anything really in social activities. I felt a little--I mean, social not as teas and so on, but as being helpful, and felt rather depressed and frustrated about it, until we went to Chappaqua(1935).

Then after my sister's(Ruth Murray, called Bay) death, when the older children--the three who are now grown up--were in school and off my hands, I went into district nursing part-time, and that satisfied my desire for being useful as well as bringing in a small--it didn't really bring in enough to notice.

Q. Would you describe yourself as a Marxist?

A. Definitely not. I have never read Marx, although what I knew of Marxist theories had a certain amount of appeal,---primarily the feeling that they were--the socialists, I mean, ---working for the betterment of people in general. I guess that is really the whole point.

Q. Well, in contrast with whom?

VIII. Sara M. Flanders 63

A. In contrast with the status quo which was doing nothing, the then regime, shall we say. Well, suppose we say up until Roosevelt's inauguration, I felt those in power were doing very little, if any, for the welfare of the people who needed it.

Q. Would you describe generally you political attitude since 1933?

A. I registered as a Democrat in Chappaqua, and I have felt that I was a liberal Democrat, but I went along with Roosevelt on practically everything. I have continued to feel that Mr. Truman was doing his best. Sometimes it wasn't as good as I hoped, but in general.

Q. Will you describe for us the relationship with the Hisses, when it started, etc.?

A. I have been extremely fond of Prossie since my sister a freshman year in college. When she married Thayer Hobson, we both felt--I think all of my family felt a little distressed because he was not the kind of person that we are. He was much better dressed, and took us to front row seats to see Gilbert and Sullivan--I think it was--the night that we went there for dinner. He was just out of our financial and intellectual group I would say. It was an entirely different background. While that went on we didn't see much of Priscilla. Although we were always--we are fond of her still--and sent Christmas presents, things of that sort. But I don't remember exactly when I met Alger. All I remember is that it was -- it seemed perfectly wonderful that Timmie would now have a really satisfactory father, and it was wonderful that Prossie and he were so happy, and the whole thing had turned out so beautifully.

Q. What was wrong with Mr. Hobson? Was he a drinking man?

A. No. It was simply that he was not the kind of person that we were. When Prossie was married to him, the tow of them didn't fit into the group, you see. It wasn't that I felt that Thayer in himself would not be a good father for Timmie, but merely that since they had broken, and since Prossie had been very much alone, and that Timmie needed a father, it was wonderful to me that it should be a unite--that Timmie should have a united family.

We was them at our farm, our place in New Lebanon. What happen about that was that both families, the Fanslers and the Flanders, felt that we needed,--we were moving from one apartment to another constantly, and we needed roots for our children. So Thomas Fansler went up and bought a farm and came back with the deed in his pocket. The following spring, after we had visited them up there, I sent Moll up to do the same thing. He came back telling me which farm he had bought. It was one which I hadn't even remembered knowing. I knew I was crazy about the country, and I would be perfectly satisfied.

So the Hisses have visited either one place or the other, either at their farm or our farm, but more usually at their farm. But we always saw them.

I felt rather sad from time to time that we saw so little of them. We would go over there for dinner, and they would come over to our house for dinner en masse. All of the Flanders would go over to see the Hisses and the Fanslers, or all of the Fanslers and Hisses would come over and have dinner with us. Whereas, if they stayed with us, we would see more of them. So that the only time when we had them to ourselves, shall I say, was when Bob and Tommy were in New York, and they came and visited us. This was when Alger was in the State Department.

VIII. Sara M. Flanders 64

It was and exciting time, and it was an exciting time because of China. I kept thinking how splendid it would be to have a man from the State Department come and we would get something more than we got out of the papers, but we didn't. It was a total loss so far as that was concerned. We had a very lovely time with them.

The next time that we really saw very much of them was one weekend which was the year after Steven was born, and Jane gave us a wedding anniversary present of spending--sending us off to Washington to stay with the Hisses.

The next time we saw them was when they came to visit me in Chappaqua after Moll had left for Los Alamos by car. They came especially to stay

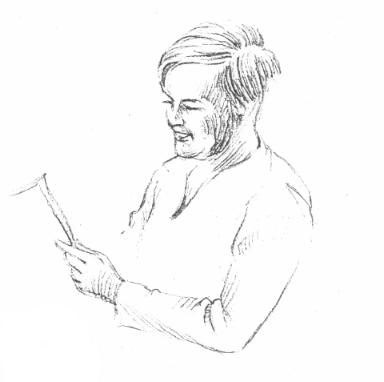

Sara M. Flanders

with me because they knew that I was going to Los Alamos. They were sorry to have missed Moll. They know we were going somewhere, and they did not know that we were going to Los Alamos.

The situation was very upsetting to me at the time. Not the Hisses, but the Los Alamos situation. We had been told that

we were not to say anything about our destination; that we were not even to know what our destination was at first. I didn't know where we were going. When Moll was offered the job, he was asked if he would take a job somewhere in the southwest. When he told me about it, I said, "Oh my goodness? Is this going to be another case of Lubbock?" That was one of the most unattractive towns that I ever spent a winter in. I said if it was as interesting a job as that, as had been said to him that it was, of course we would go.

So when we were talking about going, in Chappaqua, among my friends, before Moll left, I was saying, "I don't know where we are going, but it is just like a detective story. We don't know where we are going. We are going somewhere in the great southwest, and it is all very fascinating, you see."

I got a great deal of curiosity up among my friends. Then Moll got there and found that that approach was totally incorrect, and that the thing to do was simply say that he had a government job in the southwest--no, that he was going to the southwest--I don't remember exactly what it was, what the technique was at that time. But, anyway, it was totally at variance with what I had been doing.

I was very much upset as to whether I should try to remember every person to who I had told this tale, "That was just a cock and bull story," or whether I should keep my mouth shut.

I opened the letter. I can still see us sitting around having mid-morning coffee, and I had been down to get the mail. I was simply flabbergasted. We were, each of us, reading our mail. I said to myself, I have go to have advice. If I can't get the proper kind of advice from as close-mouthed a lawyer as I know Alger to be, and a member of the State Department, I didn't know where I could get better.

I asked Alger, not telling him any more than simply that I had made these statements to various friends, I was now to make these new batch of statements, and what should I do. Should I try to remember all of the people to whom I had made the statements, or should I just keep my mouth shut. Alger said, "For heaven's sake. Don't say anything."

Q. Did he at the time indicate that he knew where your husband was?

A. No, he didn't. He didn't ask. I mean, even at that point I had acquired the habit of not asking questions, and certainly Alger wouldn't ask a question when he knew there was any reason for not asking.

Q. You are the one who ordinarily conduct the correspondence of the family?

VIII. Sara Flanders 65

A. We have always divided up jobs, and things that I do like that (indicating), I do. Things that have to be done remarkably well, he does; things that are done with precision and care like gluing a valuable piece of furniture together. I have written all family letters with the exception of one, the Bevingtons and one, Mother Flanders. Up to this summer, I don't know of any others that he has written.

With the Hisses, it is just about the same. I would send them a Christmas present or write and say thank you for their Christmas present. I would write and say, "We are going to be in Norwich the 25th of June, "or what have you," and would it be all right with you if we stopped on the way back to the next place?" They would write back, couldn't you make it the day before or the day after, or certainly that will be fine, as the case may be. That is practically the total of our correspondence.

I have written Prossie since the trial. I have tried to write cheery letters about what Steve was doing, things like that, since Alger was put in jail.

While we were in Los Alamos, I wrote as I wrote to other friends, probably once or twice a year, aside from a thank you note at Christmas time. I said we sung carols or something of the sort, simply about the general type of activities we were engaged in, social activities, and my work in the nursery school, so on. It was probably not more that a couple of times in each year. It is quite possible that it was only in reply, in thanking her for the Christmas present.

***

After Hiroshima, everybody know that was what we were doing, and it wasn't necessary for me to write and say, "Now you see?" Everybody knew. I have no recollection of writing to anyone and saying, "See, this is what we did, " because it was obvious to everyone. I don't think we received any letters saying, "Now we know." It was just such an obvious thing.

***

I felt that the Hisses were always very much concerned about the general welfare. Priscilla and I, being somewhat more sentimental than our husbands, thought the small amount we could do was sufficiently valuable to put an awful lot of work in it. Whereas our husbands were very much interested and in sympathy with our aims, but perhaps didn't feel that what we were doing was more than a drop in the bucket, and was not as useful as we thought it was. Certainly, I would feel that Alger was a liberal in the best sense of the word, and that he hadn't a vague tinge of pink, in any snes.

I definitely remember something that I vaguely thought they should have brought out at the trial. When my sister was working in the education department at the Metropolitan Museum Bobby), she was visiting the Hisses. She said she had spoken to Prossie about a friend of her's who was a very fine sculptress living in Washington. Prossie said she would love to meet her. When Bob said, Prossy said, "I hat case, I don't want to meet her. A man in the State Department has no right to meet communists." That is the only time I know, secondhand, of any mention of communists.

Q. What is your idea of the necessity for a security program?

A. It seems unfortunate that it is necessary or that it should be necessary for there to be any secrecy about scientific work. I think science in general goes on--it has been a wonderful thing, the rapport between scientists here and in other countries, and between scientists in one place and another in the Unite State. It has been a very excellent and wonderful thing. It is too bad, it seems to me, that it should be necessary to curb that, but I do feel quite definitely that in case of anything pertaining to military ends that it is necessary and that it is reasonable that hearing such as this should be held.

VIII. Sara Flanders 66

Q. That hasn't always been your opinion, has it?

A. You are referring to the statement about the communist witch hunt, aren't you? I felt strongly then, and I still feel strongly, that McCarthyism was smearing people without basis,

and they were not being, the hearings were not being held in secret. The man was smeared by the very fact that he was being investigated. That was not a question of a so-called sensitive occupation. In other words, I felt that the un-American activities Committee was damning people without--in the public prints.

Q. Can you name one person who was in any way mistreated or unfairly handled?

A. There were saying there were thousands of people in various places, in various jobs that were disloyal, and when it came down to being investigated, maybe there was one or two.

Now, I made the distinction then, and I make it now, that when you take a job in a "sensitive" field you expect to be cleared before you take the job. You expect to be under more or less continuous scrutiny thereafter. I have expected ever since the conviction of Alger Hiss that my husband's clearance would be questioned. I mean that it didn't seem unfair that it should be. I have never felt that our love for Alger was a contradiction of my husband's fitness to work for the AEC. My husband has never told me anything that he shouldn't. Why should he tell Alger?

***

Remington lost his job because he was condemned without a hearing.

Q. There was not a criminal charge involved there, was there? None of us has a particular right to demand a particular job.

A. Nobody has a right to demand a job in a sensitive area, but the fact that this man was publicly accused before he was proven guilty--

Q. It is done in every criminal case. A grand jury returns an indictment, and it is publicized.

A. All right. There was more publicity about that, and the man would have been unable, if he had resigned -- of course, I don't remember all of these things. If he had resigned more or less at the first, he would still have found it difficult to get a job almost anywhere.

Q. Isn't that true of any man? I may be wrongfully indicted for a serious offense. I may be acquitted the next day, but still the indictment was publicized before I made any effort to make my defense. I can't see why you can do it in a criminal case, and why it wouldn't be just as proper to do it in a Congressional investigation. I am trying to find out your reaction.

A. Well, there still seems to be a difference to me.

Q. Do you have the same attitude as to the communistic smears of anybody who exposes communism? Are you opposed to smear tactics on either side? So that this attitude as to the treatment of Remington would be applied to the treatment of anyone whether he was a communist or not?

A. I think so. Wasn't it Justice Holmes who said, "I will defend with my life the opportunity --" I can't quote.

VIII. Sara Flanders 67

Q. Voltaire. You understand that later Mr. Remington was convicted? You still think he was dealt with unfairly?

A. I have no convictions about Mr. Remington. I know nothing about it except what I read at the time. I am perfectly willing to admit he was, in all probability -- that he was, shall we say --

(Mr. Despres, lawyer) I think in fairness to everybody we ought to point out that the conviction was reversed. The only reason I mention it is that if we all say there is a conviction, Mrs. Flanders will accept the statement of a panel of lawyers.

Q. What we are interested in is this: We know that it is a matter of common experience that when any accusation, charge, or unfavorable statement is made about any Commie in the United States, immediately all of the transmission belts are flooded with smear tactics against anyone who has made any unfavorable statement about any communists. We want to know whether you are in that group of not; whether you have been a tool of communist propaganda or not.

A. I am certainly against communist smear tactics too.

Q. You don't think you were being used by communists to smear others, for example, to smear the un-American Activities Committee?

A. I don't believe so.

Q. You don't think you were being used by the communists to smear others. As you undoubtably know, communists are engaged in that effort.

A. I don' think that I have been in contact with any -- with anyone who could have used me in that way.

Q. Well, your sister Roberta was in contact with a communist sculptress.

A. She met an excellent sculptress in 1942. She was not interested in politics. The only reason she mentioned the woman's politics was because Alger was in the State Department, and she felt there was a possibility that it was unwise. Otherwise, she wouldn't have bothered mentioning it, no more than you would say, "She is a Republican, or a Democrat."

Q. She recommended that the Hisses meet that lay?

A. She thought that Mrs. Hiss would be interested in an excellent sculptress. Then it occurred to her that there might be some objection on the part of the Hisses, so she mentioned it. It was originally thought of as a relationship between Mrs. Hiss and a sculptress. Then my sister realized that it would involve Alger, and thought it only fair to mention it. She mentioned it, and when the objection was brought up by Priscilla, she dropped the suggestion.

Q. Did you have any idea whether Peggy Kraft was a communist?

A. I do not now have any idea whether she was a communist. She came to our house not more than twice a winter, I would say, and I once went with her to a show that she gave, some art exhibition, and she gave a little speech about the way she made a sketch. That was all. She would come to our house for supper,

VIII. Sara M. Flanders 68

and we would play in the course of the evening, and one of us would walk with her to the streetcar, or not, as the case might be.

After she told us about this trip to Mexico, not while she was telling us but afterwards, as we read about that congress in the papers, we both independently realized that the congress which she had attended in Mexico was probably under communist auspices, although it wasn't necessarily a communist --

I don't think that we have, either of us, seen her since. Ellen took the art course that you know of after that, and neither of us had any objection to the art course as an art course. We liked Peggy, but we didn't feel that we particularly agreed, and although we may not mention politics in the course of an evening, I like to feel that the people I like and see a great course of the evening. I like to feel that the people I like and see a great deal of are of the general, have the general feeling a out the world that I have. I don't expect anybody to agree with me point by point.

Q. You discussed that you felt so happy that you were closely friendly with the Hisses, especially in view of the fact that Mr. Hiss had a rather high ranking state department job, and it might give you some inside information. What did you mean by that?

A. Well, simply as an intelligent American, which I hope I am, I think I am, I want to know as much as possible about the state of the world, the state of the United States, particularly.

I would not want -- I wouldn't have thought for a moment of Alger giving me something he shouldn't have given. You see. He must have a lot of loose information which doesn't happen to get into the papers, which is perfectly legitimate. It just doesn't happen to get into the paper. That was the kind of thing I was hoping to get. Certainly, I wouldn't think of asking Alger even then, before I had my Los Alamos training in not asking questions, I

wouldn't have thought of asking Alger a question which I thought he shouldn't answer. Frequently, in talking to people at Los Alamos I have said, "Please, may I go on asking questions because I don't know which is a sensitive question, which is an improper question, not knowing enough about which is classified and what is not. It would make me feel freer if I were free to ask any question that I want to, and you just tell me, "That is one of the things I don't answer."

So I don't even remember making such a statement to Alger, because it never would occurred to me that he would tell anything he shouldn't.

Q. I think you have mellowed a little since 1949, the last hearing. You are a little more conservative than you were.

A. I am older. You try to become more tolerant as the years go on.

Q. Your husband testified that at one period he was disturbed by what he described to us as an inflexible attitude toward Russia. Does that also reflect your attitude?

A. I have always felt and still feel that anything which could be done to make living in the same world with Russia possible, as long as you don't give up any important principle, should be done. I s that statement clear?

I don't know whether it is or not. We should try our best to get along with Russia as far as we can without giving up any principle in which we believe.

Q. Is it your present opinion that we can co-exist peacefully with Russia?

A. It is my hope. I think life would be too horrible if we didn't think there was some chance of it. We can't have another war.

VIII. Sara M. Flanders 69

Q. Will you describe for us your daughter Ellen's political attitude at present, and what it has been in the past in your opinion?

A. I think Ellen agrees very strongly with me in that she would like to see conditions better for the underprivileged. I think at one point she joined the SYL thinking that perhaps this was a means of achieving that result, or that the SYL was, and decided that the SYL was not, would not not get anywhere in that line, and did not like their activities, tactics, and got out.

Q. Would you describe Ellen's relationship to Peggy Kraft?

A. At the time that Peggy was coming to our house, Ellen wasn't living with us, and didn't see her very much. When she did meet her, she liked her very much. Ellen and Peggy played a quartet with us once. Ellen liked Peggy and Peggy liked Ellen. It was after the Pan-American Labor Conference that Ellen, though again I am not sure, took this art course with Peggy, which she enjoyed very much. Peggy was an extremely god teacher. Ellen never spoke about anything -- she came home always very much excited about the art classes, and talked about them at some length. She never mentioned politics at all in connection with the classes.

Now, she may or may not have talked some politics with Peggy at that time. I don't know. I just never happened to ask her. The reason for her going was the art classes, and they were completely satisfactory.

Q. Would you have any objection to becoming a member of an organization if you knew in advance that some members of it were communists or fellow-travelers?

A. There my opinion has changed more or less completely. You see back in 1946, when we were in Chappaqua, your witch hunt question came up again. At that time, at the time of the split when ADA and PAC became separate parties instead of the one original party, which has so many letters you can't remember what they were, we joined the PCA.

I took issue with Mrs. Roosevelt's statement she did not want to belong to an organization which would admit communists or communist sympathizers. It seemed to me that you couldn't have that kind of sign on your letter-head without a certain amount of what I then called witch hunting. Therefore, I preferred to join the PCA which made no question about whether you had been or had sympathies with the communists.

The life of the Progressive Party has fairly well proved, as well as many other things, that it is unwise to join an organization which allows communists to be in it because they are almost certain to take over by fair means or foul, so that now I don't think I would knowingly join an organization which had been communistic.

Q. We have a report on which to date we have not questioned your husband involving a picketing parade on 125th Street. I don' know the date, but the report is that Dr. Flanders, joined with a group of picketers.

A. No. I am unable to cross a picket line unless I am convinced the pickets are wrong, but I don't think I have heard of my husband joining a picket line.

Mr. Flanders: I have never been in a picket line. I have never been in a protest parade.

Mrs. Flanders: I would have heard about it.

Mr. Flanders: During 1947-48, we lived in a cooperative apartment house on

VII. Sara M. Flanders 70

552 Riverside drive. It had been gutted by fire, then subdivided, and sold as cooperative apartments. I am saying this to indicate that it was not the sort of cooperative where a group of people get together with the idea of cooperating, but rather that this was a commercial pattern. The housing was made available as a cooperative. We were one of the original purchasers of an apartment in that building.

When the tenant-owners organized, I was elected president of the cooperative, and I served through that year as president.

One of the first things that we had to do was to decide on how the building was to be managed. we decided that we would try to get one of the tenants to manage the building for a fee. He would be reimbursed for his services. None of the officers of the cooperative received any money or reimbursement. This was a job which we felt we would try to handle within the cooperative it self. There were other alternatives such as hiring, engaging a management corporation to manage it. It was a good-sized building -- maybe 57 apartments.

One of the applicants for this position was a young man recently, I believer, honorably discharged from the armed services, who lived on the ground floor, and he made a very vigorous effort to get this position of operating manager.

He was not selected for the job. I, myself, did not think he was the best qualified applicant, but I do not remember that I did anything unfair in my handling of the situation. It was very clear to me that this young man held a grudge against me because of his failure to get the position.

Toward the end of our stay in that apartment house, at one of the general meetings of the whole cooperative, a proposal was made that Negroes should enter the building through the basement and be denied entrance through the front door. This was an idea that was so repugnant to me, to my concept of democratic procedure, that I expressed considerable indignation.

It is my recollection that this young man, to whom I referred, was one of the sponsors of this idea. Shortly after that, shortly after this meeting, in which this proposition was defeated, the question of my going to Chicago arose. I believer in fact, well certainly it was know that I had accepted the position at Argonne subject to clearance. I was informed by on e of the tenants that he had overheard this young man say that he was going to inform the 'FBI that I was a wild radical, and it is my belief that this allegation is due to that incident.

Q. Mrs. Flanders, I think you said life would be too horrible if we didn't think there was some chance of peaceful co-existence with Russia. When you said that, to what were you referring.?

A. Yes What I meant was, in fact, I don't see that life would be worth living if you felt it was absolutely necessary that an atomic war should come.

Q. Now, you were asked about the difference between inquiry by Congressional investigation and indictment by a court, and you referred to principles of Anglo-Saxon law. When you referred to that --

A. I don't know about them.

Q. I don't want to ask you what Anglo-Saxon law is, but what you had in mind.

A. I have in mind, well, the oft-repeated statement that until a man is proven guilty he is assumed to be innocent.

Q. What about the other rights such as the right to know the charges, the right to examine witnesses, the right to introduce evidence in your own defense.

VIII. Sara M. Flanders 71

A. Those I also assume as the rights that one should have.

Q. Those are rights that we do have in a court of law, aren't they? And many of those rights are protected also by safeguards in administrative proceedings, too, aren't they?

A. Yes.

Q. But before a congressional committee, is it your impression that a man knows the charge in advance, or that he has a right to cross-examine witnesses, or that he has a right to introduce evidence himself?

My feeling about the Dies committee procedure was that those things were not true. That is what I understand. That was the objection that I felt was valid to procedures of the Dies committee Those safeguards were not in effect.

Q. You spoke about the Remington case. You said you knew what you read about it. What had you read about the case, the newspaper accounts, I suppose?

A. I read the Herald Tribune on the subject, and I presume that the Nation had an article. The thing that impressed me was the articles in The New Yorker.

Q. And those articles dealt, with the loyalty hearing of Remington? Wasn't that in the early days of the loyalty hearings? And wasn't that some years ago, before a great many safeguards were in effect?

A. Yes.

Q. And didn't those articles describe the great difficulty that he had in knowing the charges against him? And the difficulty in meeting the evidence against him? Then, wasn't he cleared eventually in the loyalty proceeding? (Yes to all questions) Then didn't the article describe the expense to Remington of the proceeding?

A. Yes, and how he was baby-sitting, when he could get baby-sitting, with people who wouldn't feel that he was a subversive influence on their 6-month-old baby?

Q. The record with Remington so far is that there has been a loyalty charge against him, and he has been cleared of that. There has been a court trial against him, and he has been convicted, but the conviction has been reversed. Then he has been indicted, I shouldn't say the conviction has been reversed. It has been set aside. He was indicted for perjury on his first federal trial.

A. My remarks were all prior, about the situation when I understood he had been cleared. The articles in The New Yorker were heartrending.

***

I would say that it is necessary for the AEC to investigate the loyalty of all the people who work for it. I would say that having found out that one of our dearest friends is in jail, it was fairly obvious that you should take up the problem.

You state in the AEC criteria for employment that associations are important, but that it is up to you to take up such associations and view them in the light of the man's personality.

VIII. Sara M. Flanders 72

Q. Would you tell about your husband's discretion, loyalty, carefulness, his feelings about right and wrong, his principle, -- state them as you know them.

A. One reason I told you about my not know anything about this hearing was to show that even in a case where it wasn't of national importance, he could be completely secretive. He has written to me over and over this summer, and I never had the slightest ideas that there was anything going on other than the fact that life is not as easy when I am around, not as easy when I am around bothering him. All right. I would say that.

Q. I understand this.

A. Thank you. I would say that my husband is one of the three or four most honorable people I know.

When we were considering going to Los Alamos, it sounded as though living conditions would be rather bad, as though everything else would be rather bad, but the work was for the welfare of the country. That is the reason we decided to go. I mean, it is the welfare of the country rather than which side our bread is buttered on that counts.

Q. If Mr. Remington is guilty, isn't what he has done to the United States a tragic thing?

A. Definitely. I would not question that. Don't forget that my indictment, if you could call it that, of the Dies committee was not in the light of the fact that he was guilty, but in the light which seemed, well, the best light I had at the moment, which was that he was innocent. He should have been presumed to have been innocent until he was proved guilty.

Q. He want' proved guilty of anything.

A. My point about Alger Hiss is that when I know a man and believe in him as I believe in Alger, I can't agree with the verdict. My day at the trial bears out my feelings on the subject because the next day, as I read the papers, the things that I had heard at the trial which seemed to me to back up my belief in Alger's innocence were not mentioned in the paper the following day. The things that were mentioned in the paper were things which I hadn't noticed, which seemed completely unimportant to me as I listened.

Q. Your confidence in and friendship for -- I think you have described it as love for the Hisses has not been diminished by this conviction?

A. Not in the least.

Q. But that in your opinion does not mean that your spouse should be disqualified from continuing to contribute to this national effort?

A. Definitely not. I would not. My husband has never said anything to me that he should not say. Why should he say it to anyone else?

Q. I have only one question more. Do you know whether these judicial safe-guards, cross-examination, and the like, have ever been applied in Anglo-Saxon history to legislative investigations?

A. I don't know anything about legislative investigations. I don't remember having read about them until the present crop.

IX. Closing statement of Mr. Despres, lawyer for the defense 73

I would like to say that in the hearing, I have tried to do what Dr. Flanders asked to have done, and that is to handle the whole hearing not in any sense like a partisan proceeding, but like a join effort to arrive at a result and a finding.

Now, if at any time I have done anything favorable, I wish you would credit Dr. Flanders with it. If I have injected myself in any way that irritated, then i wish you would place the blame for it on me, and on my shoulders, because that was really not Dr. Flanders' intention from the beginning.

In all his conferences with me, and in his statements here, he said what he wanted was an arrival at the truth and at a good judgment. At the same time, also, in any questions I may have made, I have intended to be broad. There were times when you properly asked something broader than I had asked. I was to say my intention was never to phrase a question and get a narrow answer. For example, I asked one witness about Mrs. Flanders' character. I think the chairman properly said, "Well, Mr. Despres didn't cover loyalty." It is true; I didn't cover it it. I didn't intend to omit it. We intended cover everything. There was no attempt at trickery or the narrowing of questions.

I would like to express my appreciation to the panel for its patience, courtesy and decorum.